Blog

The Games That Children Played

I am a Baby Boomer. When I was a kid, there were no computers, tablets, cell phones, internet, or even video games. Children today cannot comprehend the fun that we had despite not having these things. We played games like tag, hide and seek, stick ball, jacks, marbles, jump rope, hula hoop, kite-flying, dodge ball, catch, pickup sticks, and board games. We played cops and robbers, house, played with dolls and toy cars, rode our tricycles, scooters and bikes, climbed trees and played in mud puddles. A generation later, my own children enjoyed a lot of these same activities.

Superstitions

We all know about the bad luck that walking under a ladder or a black cat crossing your path can supposedly bring. What about breaking a mirror and having seven years of bad luck as a consequence? I remember being at the home of my friend Laurie when I was about twelve and accidentally breaking a mirror. I was devastated to think that I would have bad luck until I turned nineteen. That seemed like forever!

Secret Babies

Piropos

Who doesn’t like a sincere compliment? “You’re a good cook,” “I like the way you decorated this room,” “Your children are well behaved,” “You are a talented musician,” or any such positive comments have always been a pleasure to hear.

Piropos are not quite the same and never did sit well with me. One definition of the term says that it is a flattering comment or compliment. Well, yes, it could be. But in Spanish-speaking countries piropos quite often are “unsolicited flirtatious or sexually oriented comments made by a male to a passing female of reproductive age whom he does not know.”

Are ALL Puerto Ricans Related?

Years ago, on American Idol there was a Puerto Rican contestant named Tatiana Del Toro. She could obviously sing or she wouldn’t have made it to the top 36. Tatiana was sometimes dramatic and annoying, but I remember her also for a comment that she made about Puerto Ricans: “We are all cousins.” While that’s a standard joke that we Puerto Ricans have, it sometimes seems to be true.

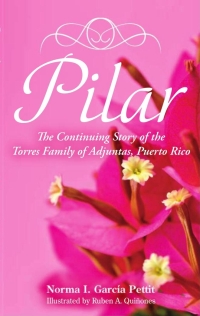

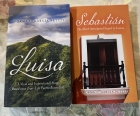

DNA Cousins Are Both Authors

If you have done your DNA test on Ancestry, you know that you have a list of matches that is broken down into close relatives, first cousins, 2nd-3rd cousins, 4th-6th cousins, etc. Those of us genealogy addicts that are on Facebook refer to the distant cousins as “DNA Cousins”. Back in July, I was contacted by one such DNA cousin, Marisol Colón Santoni. She told me about her friend, Donna Darling, who (like me) wrote a historical novel based in Adjuntas, Puerto Rico. However, Donna’s book, The 3 Marias, is set around 1897-1900, while my book, Luisa, is set from 1867-1870. Marisol thought that it would be fun for the three of us to get together and talk about genealogy and our books.

Guessing Someone's Age

Ponce's Architecture in 1870

Quenepas - Tasty but Dangerous

Ponce is famous for its quenepas, a very tasty fruit extremely rich in phosphorus and iron. In fact, it is the city’s official fruit and Ponce hosts an annual quenepa festival in the town plaza. Of course, I had to include something about them in Sebastián. Here is an excerpt from Chapter 19.

The Barrio of the Freed Slaves

The setting for Sebastián is in Ponce, Puerto Rico from September 1870 to September 1871. Even though slavery in the United States had been abolished since December 6, 1865, Puerto Rico was still a colony of Spain at that time. Under Spanish rule, slavery on the island still existed, although it was nearing its end. Sebastián Torres, born and raised in the mountains of Adjuntas, had never even seen a slave until moving to Ponce and visiting the barrio of San Antón.

Do You Know What These Are?

These are ditas, or traditional Puerto Rican bowls. The larger, oblong bowls are made from the gourd-like fruit of a calabash tree called the higüero. The smaller ones are made from the dried out shell of a coconut. The Taíno Indians constructed different types of domestic items, such as bowls and cups, and this practice survived well into the twentieth century, especially in rural areas of the island.

Ponce’s Famous Ceiba Tree

In the center of this small park there was—surprise! – a ceiba tree of significant historic importance. It is

believed to have already been a large tree at the time of the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1493. In

the areas surrounding this tree, broken indigenous pottery, shells, stones and other evidence of the

presence of Taíno Indians have been found. In fact, the name ceiba comes from a Taíno word. Legend

says that underneath the massive tree's canopy, the Taínos celebrated their religious rites. It is also

believed that the first European settlement in the Ponce region was right in that very area, next to the

Río Portugués. Later, slaves purportedly danced under that tree when the harvest seasons ended.

Washing in the Creek

On our recent trip to Puerto Rico, we took our customary drive to Guavate for some lechón asado – roast pork. It was a harrowing drive because there were at least a dozen large mudslides along the way, results of Hurricane Fiona. We bought a few souvenirs and then had lunch at our favorite restaurant, Lechonera Los Pinos. I took a picture of their mural depicting women washing clothes in the creek.

The Mango Tree Incident

On our walk today we passed a mango tree that still had a couple of green mangos on it, despite the season having passed. I was reminded of a story that my father, Oscar, told me many years ago.

He was a young child, living in Barrio Santo Domingo in the mountain town of Peñuelas. He must have been only about seven or eight years old because he was still in school, and I know that he only studied until the third grade.So Much Flavor!

In the San Juan area, a nickel is called un vellón de cinco – a five cent coin, but in Ponce it is called una ficha. In some places un caldero is known as una olla, and what you call it could depend on the size of the pot or what it is used for. Ice cream can be called mantecado or helado, and we already talked about the controversy between empanadillas and pastelillos. For me, una funda is a pillowcase and una bolsa is a bag. But in some parts of the island, una funda is another word for a bag.

Pastelillos or Empanadillas?

Mal de Ojo (Evil Eye) and Other Superstitions

My introduction to this belief came with a conversation that I had with an elderly family member some fifty years ago. She was telling me about her little daughter that had died as a tot. She had been a beautiful child with abundant curly hair, but she got sick and died quite suddenly. When I asked about the cause of death, the woman firmly declared that her daughter had received the evil eye from a jealous neighbor woman.

Café con Leche

What Are the Odds of This Happening?

When a casual conversation leads to discovering a distant relative…

We rent out our Puerto Rico home as a short term vacation rental. Recently, a couple rented it for an entire month. The day before they left, the lady casually mentioned that they had visited Adjuntas because their daughter’s neighbor was from that town. That prompted me to tell her that my mother was born in Adjuntas and that I had written a book based on my great-grandmother’s family. I was curious as to what part of Adjuntas her daughter’s neighbor was from. She inquired and reported back to me that Joana’s family was from Juan González, the same as my ancestors!

If You Thought Ironing Is a Chore Now...